NAVIGATION: BACK TO MODULE TWO INTRODUCTION

Differential Weathering

and Scarp Retreat

Differential

Weathering:

Rock does not weathering

uniformly due to variations in local and regional factors. Weathering becomes interesting,

in terms of its manifestation in form across the landscape, when rocks weather

differentially - differential weathering can produce spectacular landforms and

landscapes.

The canyon walls in the Grand Canyon are a series of

uniquely shaped "steps". The steps are actually different strata

or different rock types. Some of the layers of rocks weather very easily

(are not very resistant) while others weather very slowly (are very

resistant). The rocks that weather very easily (like mudstones and shales)

generally tend to form gentle ramps into the canyon below. The rocks that weather

very slowly, i.e., the rocks that are highly resistant to weathering, generally tend to

have much steeper slopes - some approach a 90 degree slope (vertical).

|

"Steps" in the Grand

Canyon. |

|

|

| Differential weathering in the Painted Desert (not too

far north of Flagstaff, AZ). See the resistant rock (the layer

that is making the shadows). Notice how the weaker layers (least

resistant) have the most gentle profiles along the ridge. |

|

|

|

| Here's a profile of JFK in basalt. If it were not for

differential weathering, we would see this profile as merely a pile of

rocks. This image was borrowed from here. |

So far we have talked about differential weathering in terms of variations in

the resistances in strata as seen on a scarp or cliff face (such as the walls of

the grand canyon). Other conditions that yield distinctive landforms are

resistant cap rocks. A more

resistant cap rock (such as sandstone) at the top of a mesa does not weather or

erode until the softer underlying rock weathers and erodes away - when the

underlying rock is no longer supporting the cap rock, it will break away and

fall down the slope of less resistant underlying rock.

|

|

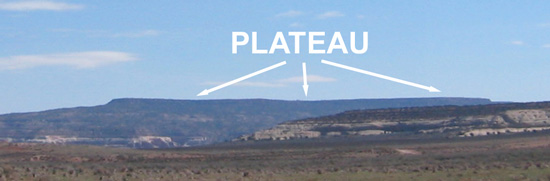

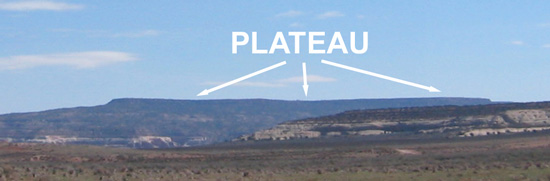

| The plateau in the above

image is covered with a flat protective rock (probably basalt).

The protective rock is called a "cap rock". Cap rocks

protect weaker layers below from erosion. |

Other examples of differential weathering are Devil's Tower, Wyoming and

weathering forms controlled by jointing.

Devils

Tower, Wyoming. Devil's Tower is a very resistant "volcanic

plug" that was surrounded by weaker shales that have since eroded

away. All that is left is the resistant tower. Devils

Tower, Wyoming. Devil's Tower is a very resistant "volcanic

plug" that was surrounded by weaker shales that have since eroded

away. All that is left is the resistant tower. |

| |

The profile

through this rock is loaded with fractures or joints. The joints

or breaks in the rock give weathering a head start... the

increased surface area in the joints lead to accelerated weathering

along the joints. This diagram borrowed from here. The profile

through this rock is loaded with fractures or joints. The joints

or breaks in the rock give weathering a head start... the

increased surface area in the joints lead to accelerated weathering

along the joints. This diagram borrowed from here. |

Scarp Retreat:

The Colorado Plateau is

full of cliffs (cliffs and scarps are synonymous, but scarp is a cooler word

than cliff). Cliffs weather and erode, just like anything... but, because

they are vertical faces of rock, we say that they, "retreat".

How does this work, you ask?

The image here shows a typical scarp. As it weathers and material falls

down the steep face and piles up at the base, the whole scarp tends to

"retreat" (scarp retreat) from left to right. The material that weathers is

eroded away; exposing the next surface to be weathered. The cycle

continues and the scarp continues to retreat. If you had a time lapse

video of this area (say, a picture taken every 100 years), the scarp would

eventually march out of the image and you would only see a flattish plane (that

transports away the weathered material) and the blue sky.

The image here shows a typical scarp. As it weathers and material falls

down the steep face and piles up at the base, the whole scarp tends to

"retreat" (scarp retreat) from left to right. The material that weathers is

eroded away; exposing the next surface to be weathered. The cycle

continues and the scarp continues to retreat. If you had a time lapse

video of this area (say, a picture taken every 100 years), the scarp would

eventually march out of the image and you would only see a flattish plane (that

transports away the weathered material) and the blue sky.

John and I think the

reason the scarp retains a nearly "vertical" or very steep surface as

it retreats is as follows: Weaknesses in the layers of rock serve as a

"failure" zone... In other words, in this image, there is a very weak

layer of strata near the base of the cliff that erodes very easily. Once

the weak layer has eroded, there is no longer any "support" for the

main cliff face -- the cliff becomes undermined. After it is undermined,

the next segment of rock fails and breaks away and falls down the side of the

slope. The process continues and the scarp retreats.

Devils

Tower, Wyoming. Devil's Tower is a very resistant "volcanic

plug" that was surrounded by weaker shales that have since eroded

away. All that is left is the resistant tower.

Devils

Tower, Wyoming. Devil's Tower is a very resistant "volcanic

plug" that was surrounded by weaker shales that have since eroded

away. All that is left is the resistant tower. The profile

through this rock is loaded with fractures or joints. The joints

or breaks in the rock give weathering a head start... the

increased surface area in the joints lead to accelerated weathering

along the joints. This diagram borrowed from

The profile

through this rock is loaded with fractures or joints. The joints

or breaks in the rock give weathering a head start... the

increased surface area in the joints lead to accelerated weathering

along the joints. This diagram borrowed from  The image here shows a typical scarp. As it weathers and material falls

down the steep face and piles up at the base, the whole scarp tends to

"retreat" (scarp retreat) from left to right. The material that weathers is

eroded away; exposing the next surface to be weathered. The cycle

continues and the scarp continues to retreat. If you had a time lapse

video of this area (say, a picture taken every 100 years), the scarp would

eventually march out of the image and you would only see a flattish plane (that

transports away the weathered material) and the blue sky.

The image here shows a typical scarp. As it weathers and material falls

down the steep face and piles up at the base, the whole scarp tends to

"retreat" (scarp retreat) from left to right. The material that weathers is

eroded away; exposing the next surface to be weathered. The cycle

continues and the scarp continues to retreat. If you had a time lapse

video of this area (say, a picture taken every 100 years), the scarp would

eventually march out of the image and you would only see a flattish plane (that

transports away the weathered material) and the blue sky.